The case against `git cherry pick`: Recommended branching strategy for multi-environment dbt projects

This blog post was written before Staging environments. You can now use dbt Cloud can to support the patterns discussed here. Read more about Staging environments.

Why do people cherry pick into upper branches?

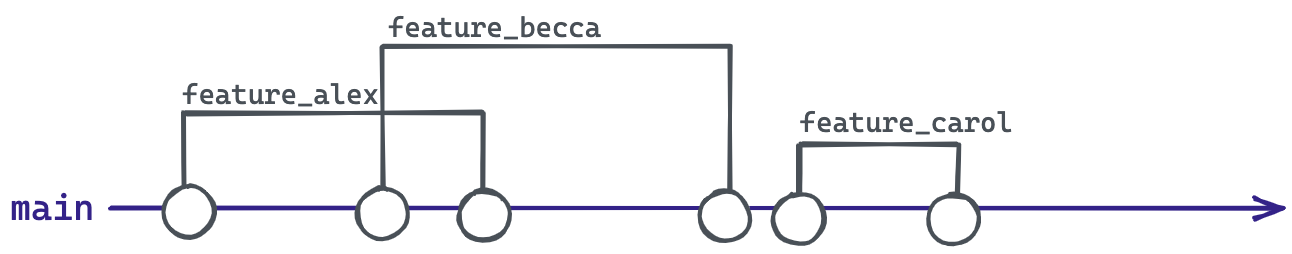

The simplest branching strategy for making code changes to your dbt project repository is to have a single main branch with your production-level code. To update the main branch, a developer will:

- Create a new feature branch directly from the

mainbranch - Make changes on said feature branch

- Test locally

- When ready, open a pull request to merge their changes back into the

mainbranch

If you are just getting started in dbt and deciding which branching strategy to use, this approach–often referred to as “continuous deployment” or “direct promotion”–is the way to go. It provides many benefits including:

- Fast promotion process to get new changes into production

- Simple branching strategy to manage

The main risk, however, is that your main branch can become susceptible to bugs that slip through the pull request approval process. In order to have more intensive testing and QA before merging code changes into production, some organizations may decide to create one or more branches between the feature branches and main.

Before adding additional primary branches, ask yourself - "is this risk really worth adding complexity to my developers' workflow"? Most of the time, the answer is no. Organizations that use a simple, single-main-branch strategy are (almost always) more successful long term. This article is for those who really absolutely must use a multi-environment dbt project.

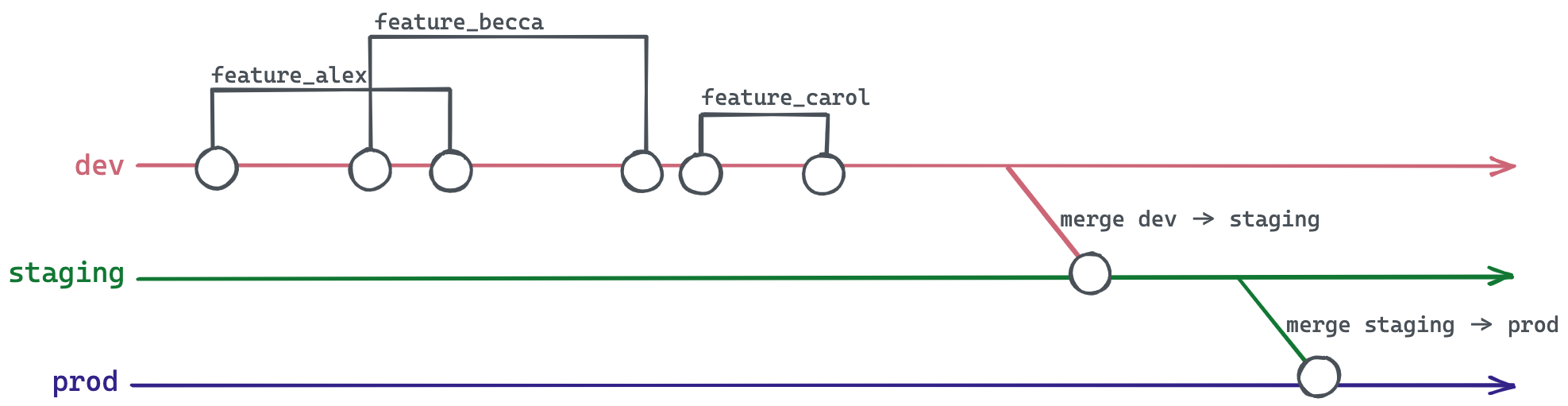

For example, a single dbt project repository might have a hierarchy of 3 primary branches: dev, staging, and prod. To update the prod branch, a developer will:

- Create a new feature branch directly from the

devbranch - Make changes on that feature branch

- Test locally

- When ready, open a pull request to merge their changes back into the

devbranch

In this hierarchical promotion, once a set of feature branches are vetted in dev:

- The entire

devbranch is merged into thestagingbranch

After a final review of the staging branch:

- The entire

stagingbranch is merged into theprodbranch

While this approach—often referred to as “continuous delivery” or “indirect promotion”—is more complex, it allows for a higher level of protection for your production code. You can think of these additional branches as layers of protective armor. The more layers you have, the harder it will be to move quickly and nimbly on the battlefield, but you’ll also be less likely to sustain injuries. If you’ve ever played D&D, you’ll understand this tradeoff.

Because these additional branches slow down your development workflow, organizations may be tempted to add more complexity to increase their speed—selecting individual changes to merge into upper branches (in our example, staging and prod), rather than waiting to promote an entire branch. That’s right, I’m talking about the beast that is cherry picking into upper branches.

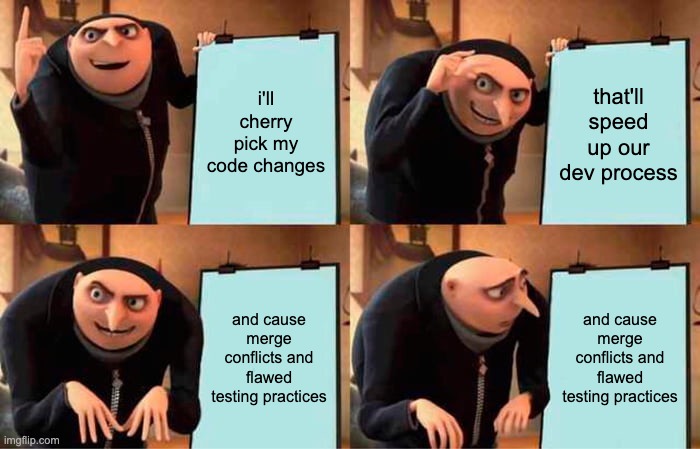

git cherry-pick is a git command that allows you to apply individual commits from one branch into another branch.

In theory, cherry picking seems like a good solution: it allows you to select individual changes for promotion into upper branches to unblock developers and increase speed.

In practice, however, when cherry picking is used this way, it introduces more risk and complexity and (in my opinion) is not worth the tradeoff. Cherry picking into upper environments can lead to:

- Greater risk in breaking hierarchical relationship of primary branches

- Flawed testing practices that don’t account for dependent code changes

- Increase chance of merge conflicts, draining developer time and prone to human error

If you’re not testing changes independently, you shouldn’t promote them independently

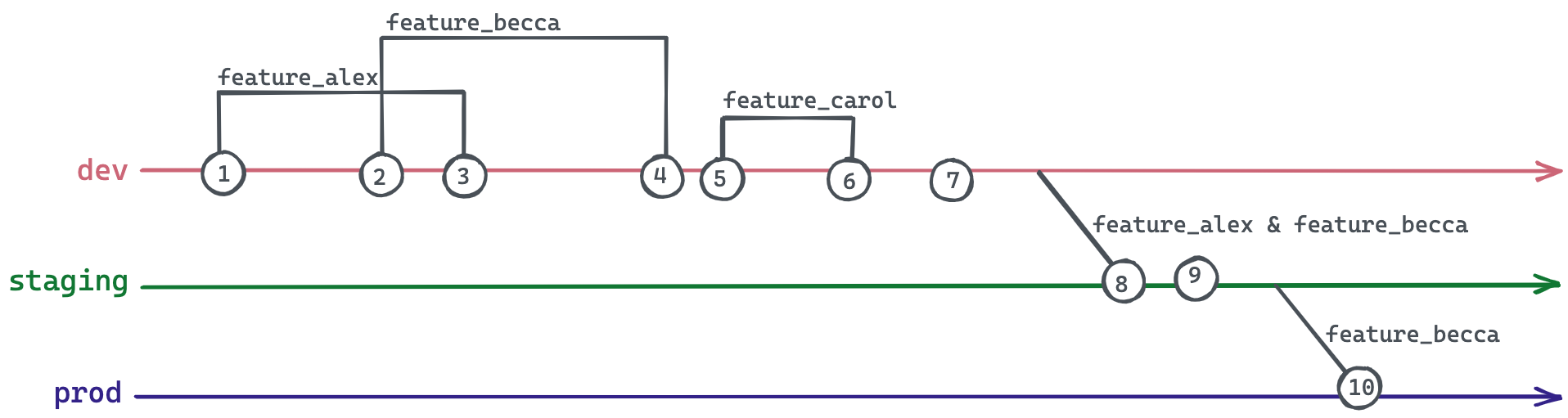

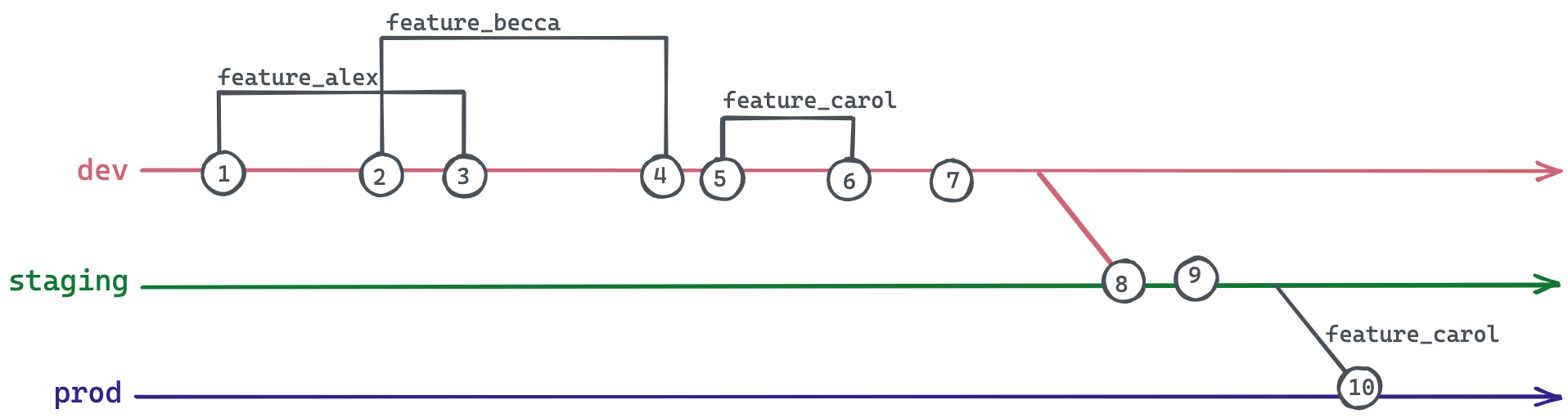

If you’ve attempted a branching strategy that involves cherry picking into upper environments, you’ve probably encountered a scenario like this, where feature branches are only tested in combination with others:

- Alex wants to make a code change, so they create a new branch from

devcalledfeature_alex - Becca has a different code change she’s working on, so she creates a new branch from dev called

feature_becca - Alex’s changes are approved, so they merge

feature_alexintodev. - Becca’s changes are approved, so she merges

feature_beccaintodev. - Carol is working on something else, so she creates a new branch from

devcalledfeature_carol. - Carol’s changes are approved, so she merges

feature_carolintodev. - The testing team notices an issue with Carol’s new addition to

dev. - Alex and Becca’s changes are urgent and need to be promoted soon, they can’t wait for Carol to fix her work. Alex and Becca cherry-pick their changes from

devintostaging. - During final checks, the team notices an issue with Alex’s changes in

staging. - Becca is adamant that her changes need to be promoted to production immediately. She can’t wait for Alex to fix their work. Becca cherry-picks her changes from

stagingintoprod.

What’s the problem?

In the example above, the team has only ever tested feature_becca in combination with feature_alex —so there’s no guarantee that feature_becca’s changes will be successful on their own. What if feature_becca was relying on a change included in feature_alex? Because testing of branches is not conducted independently, it’s risky to merge independently.

Feature branches contain more than meets the eye

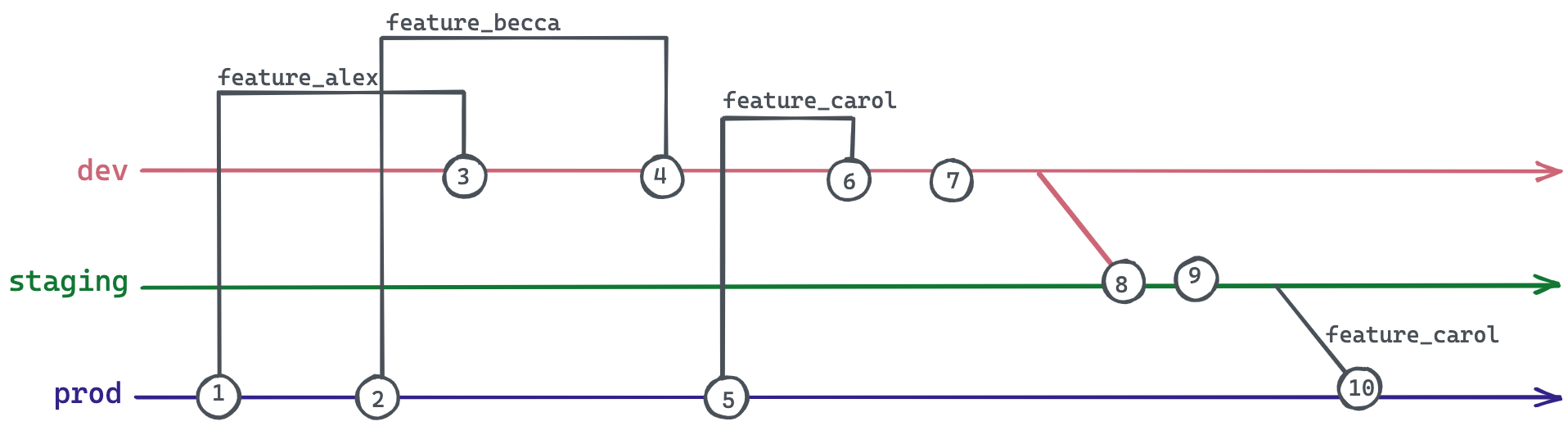

Let’s imagine another version of the story, where Carol’s changes are the only ones that are ultimately merged into prod:

- Alex wants to make a code change, so they create a new branch from

devcalledfeature_alex. - Becca has a different code change she’s working on, so she creates a new branch from

devcalledfeature_becca. - Alex’s changes are approved, so they merge

feature_alexintodev. - Becca’s changes are approved, so she merges

feature_beccaintodev. - Carol is working on something else, so she creates a new branch from

devcalledfeature_carol. - Carol’s changes are approved, so she merges

feature_carolintodev. - The testing team approves the entire

devbranch. devis merged intostaging.- During final checks, the team notices an issue with Alex and Becca’s changes in

staging. - Carol is adamant that her changes need to be promoted to production immediately. She can’t wait for Alex or Becca to fix their work. Carol cherry-picks her changes from

stagingintoprod.

What’s the difference?

Because feature_carol was created after feature_alex and feature_becca were already merged back into dev, feature_carol is dependent on the changes made in the other two branches. feature_carol not only contains its own changes, it also carries the changes from feature_alex and feature_becca. Even if Carol recognizes this and only cherry-picks the individual commits from feature_carol, she’s still not in the clear because of the previously mentioned testing dependency. feature_carol’s commits have only ever been tested in combination with feature_alex and feature_becca.

Repeated merge conflicts drain development time

In order to avoid this dependency issue, your team might have the idea to create feature branches directly from prod (instead of dev). If we imagine the previous scenario with this alteration, however, we can easily see why this doesn’t work either:

- Alex wants to make a code change, so they create a new branch from

prodcalledfeature_alex. - Becca has a different code change she’s working on, so she creates a new branch from

prodcalledfeature_becca. - Alex’s changes are approved, so they merge

feature_alexintodev. - Becca’s changes are approved, so she merges

feature_beccaintodev. - Carol is working on something else, so she creates a new branch from

prodcalledfeature_carol. - Carol’s changes are approved, so she merges

feature_carolintodev. - The testing team approves the entire

devbranch. devis merged intostaging.- During final checks, the team notices an issue with Alex and Becca’s changes in

staging. - Carol is adamant that her changes need to be promoted to production immediately. She can’t wait for Alex or Becca to fix their work. Carol cherry-picks her changes from

stagingintoprod.

Now, feature_carol only contains its individual changes—the team can merge her branch independently into dev, staging, and ultimately prod without worrying about accidentally pulling along the changes from the other two branches.

What’s the problem?

A new issue emerges, however, if feature_alex or feature_becca alter the same lines of code as feature_carol. When feature_carol is merged into each of the primary branches, Carol will have to solve merge conflicts every time in the exact same way to ensure the hierarchy of the branches remain consistent. This takes time and is prone to human error.

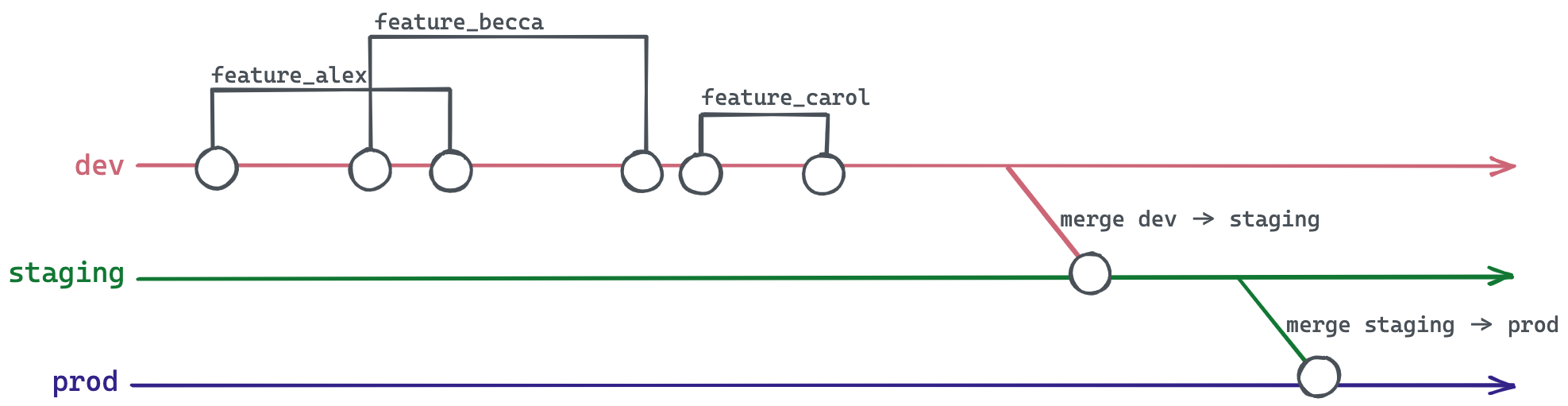

What to do instead: The recommended branching strategy for multi-environment dbt projects

In the end, cherry picking into upper branches is a branching strategy that causes more trouble than it’s worth.

Instead, if you decide to use a branching strategy that involves multiple primary branches (such as dev, staging, and prod):

- Protect your

devbranch with a dbt cloud CI job - Ensure thorough code reviews (check out our recommended PR template)

- Only promote each primary branch hierarchically into each other

If issues arise during testing on the dev or staging branch, the developers should create additional branches as necessary to fix the bugs until the entire branch is ready to be promoted.

As mentioned previously, this approach does have a clear disadvantage—it might take longer to fix all of the bugs found during testing, which can lead to:

- Delayed deployments

- Code freezes on

dev, creating a backup of out-dated feature branches waiting to be merged

Thankfully, we can mitigate these delays by doing rigorous testing on the individual feature branches, ensuring the team is extremely confident about the change prior to merging the feature branch into dev.

Additionally, developers may supplement the above workflow by creating hotfixes to quickly resolve bugs in upper environments

A hotfix is a branch that is created to quickly patch a bug typically in your production code. If a high-stakes bug was discovered in prod, a hotfix branch would be created from prod, then merged into prod as well as all subordinate branches (dev and staging) once the change has been approved. Similarly, if a high-stakes bug were discovered in staging, a hotfix branch would be created from staging, then merged into staging as well as all subordinate branches (dev) once the change has been approved. This allows you to fix a bug in an upper environment without having to wait for the next full promotion cycle, but also ensures the hierarchy of your primary branches is not lost.

Even with its challenges, hierarchical branch promotion is the recommended branching strategy when handling multiple primary branches because it:

- Simplifies your development process: Your team runs more efficiently with less complex rules to follow

- Prevents merge conflicts: You save developer time by avoiding developers having to manually resolve sticky merge conflicts over and over

- Ensures the code that's tested is the code that is ultimately merged into production: You avoid crisis scenarios where unexpected bugs sneak into production

Now I’ll admit it: this blog post was mostly just a venting session, providing me a cathartic outlet to rage against cherry picking (my Slack dms are open if you want to see all of the memes that didn’t make it into this post).

And you may be left thinking… ok, jeez Grace, I won’t cherry pick into upper branches. But how do I actually set up my dbt project to properly use hierarchical branch promotion?

Don’t worry, a guide and training course are on the way ;)

Comments

Error loading comments. Please try again later.